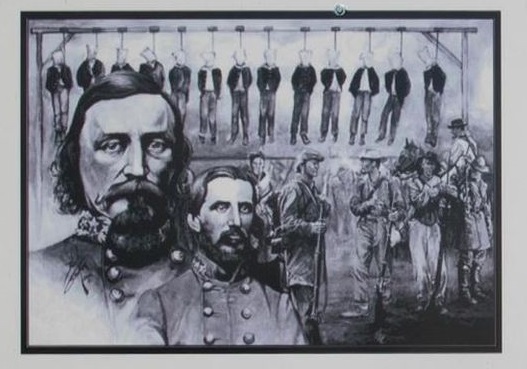

And the Confederate Army hanged them for it.

“You are aware, my friends, that I have given public notice that upon this occasion I would preach a funeral discourse upon the death of the twenty-two unfortunate, yet wicked and deluded men, whom you have witnessed hanged upon the gallows…”

Reverend John Paris, in a sermon before Hoke’s confederate brigade at Kinston, North Carolina on February 28, 1864. [1]

“These men, in thus refusing… to aid a traitorous cause, could not have had any of that guilt which constitutes desertion. The word desertion, in a military sense, implies guilt and crime, but assuredly the abandonment of a rebel cause is neither guilt nor crime; but, on the contrary, it is a merit and virtue, and ought to be so held…”

Brigadier General Rushton C. Hawkins, US Army, An Account of the Assassination of Loyal Citizens of North Carolina, for Having Served in the Union Army. [2]

Shaping the Narrative

American patriot, abolitionist, and yes, former slave, Frederick Douglass saw fit to devote more than a few words in his autobiography to the evils of slavery. Among them are these:

“My mistress was, as I have said, a kind and tender-hearted woman; and in the simplicity of her soul she commenced, when I first went to live with her, to treat me as she supposed one human being ought to treat another… Slavery proved as injurious to her as it did to me… Under its influence, the tender heart became stone, and the lamblike disposition gave way to one of tiger-like fierceness.”

Excerpt from chapter VII, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass [3]

It was a brilliant rhetorical device, for he well knew that the true victims of slavery were those actually enslaved. But he also knew that his audience of white northerners was, on the whole, generally ambivalent to the plight of those in bondage. Even those who would never desire to hold a slave themselves were liable to think it was for the best that people of color were kept in bondage. And some were outright terrified at the prospect of what a rush of suddenly free former slaves migrating to manufacturing jobs in the North might do to their own, already threadbare, standard of living. So Douglass didn’t only ask them to have pity for the slave–at least not exclusively. He put forward the idea that people like themselves–white folk in the south–might be holding slaves at the hazard of their own humanity. In short, he asked his audience to consider the horrible affects of slavery on the slavers, to take pity on those poor wretches saddled with the burden of administering the institution of slavery, and all the moral injuries it entailed for them.

Sometimes it helps to consider how oppressive systems may do harm even to a favored class.

Shades of Blue

Blue is to North as Gray is to South. That’s the narrative most high school students–probably most college students, too–walk away from their Civil War history lessons with. To the extent there may be some nuance injected into the standard narrative, it’s much more likely that the emphasis will be on men from border states like Kentucky or Maryland–states where slavery was allowed but that remained with the Union–who went off to join the Confederacy than the other way around. One tends not to hear of southerners lending their support to “the other side.” But it happened.

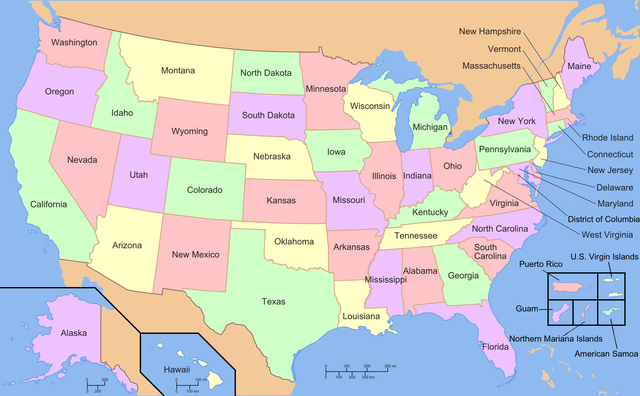

First, there’s the elephant in the room: roughly 3.5 million men, women, and children who had virtually no say in the matter of who to support at all as they were kept enslaved, to be bought and sold and passed down from father to son like property. [4][5] But even among those who were not viewed by the ruling class of white supremacists as property, support for secession was, at the very least, not unanimous. For proof of this assertion, one need only look at a map of the United States as drawn today.

I direct your attention now to the eastern seaboard of the United States of America. Right along the middle of that coastline, about midway between the southern tip of Florida and the northern tip of Maine, there is a state called Virginia. If you put your finger right on those words as printed on the map–Virginia–and then let that finger trace a path up and to the left a little, towards Ohio (but stop before you get there), you will find it come to rest on a yellow blob representing the intriguingly named state of West Virginia. This somewhat unoriginally named state came about as a direct consequence of the Virginia state convention held in Richmond in April of 1861, when a majority of delegates voted unlawfully to secede from the Union. This was in spite of the near-unanimous opposition of the delegates from all the Virginia counties west of the Alleghanies (towards Ohio, which Virginia used to share a border with). Consequently, on June 11 of that momentous year, delegates of those same western counties got together in Wheeling, set up a shadow government–a sort of government in exile opposed to the secessionist government in Richmond–and seceded from Virginia in turn. Bordering four states that would remain loyal to the Union, and only Virginia on the rebel front, these counties were thus able to extricate themselves from the unconstitutional and unlawful treachery of the Richmond government and ultimately gain statehood under the protection of the Union Army.[6]

Even in the deep south, where anti-secession counties would have been surrounded by rebel territory on all sides, there were islands of Unionist sentiment. In my home state of Texas, for instance, 18 out of 122 counties voted against secession.[7] Although the standard narrative is that poor southern men (holding no slaves) were eager to fight off the invading Union Army–“to defend their homes,” we are told–the reality is that few enough southern men were willing to die for the benefit of wealthy slaveholders that the rebel government in Richmond found it necessary to pass the Conscription Act of 1862, in which all white men between the ages of 18 and 35 were liable for three years of military service, with the upper limit on age increased to 45, and then again to 50 as rebel leaders found it necessary to send more and more men away from their homes and families to die for the preservation of slavery (and of course plantation-owners with more than twenty slaves could be exempted from conscription, because someone needed to keep the slaves down on the plantation, that’s what they were fighting for).[8] Curiously, the much less sweeping Enrollment Act, passed by the lawful federal government a year later, is much more frequently the target of criticism for its own less than equitable nature, allowing the wealthy to buy their way out of the draft.[9] It’s almost as if there has been a concerted effort by some historians to shape a narrative of the Civil War in which secession is supposed to have been provoked not by the desire of a few wealthy white men to own their fellow human beings as property, but by much higher minded ideals like “states rights” and “freedom,” such that we must ignore just how oppressive the rebel government really was, even towards free white men who didn’t have enormous wealth and property.[10] But I digress…

The rebel Conscription Act of 1862 was sufficiently unpopular that many men resisted, and not least of all in those counties that wanted nothing to do with secession. In Cooke County, for instance–one of the eighteen Texas counties where even the free white men permitted to vote did not see their interests aligned with the rebels–rebel troops arrested 150 Unionists and, according to majority vote by a “citizen court” made up mostly of slaveholders in a county where fewer than 10% of households held slaves, hanged forty men on charges of treason and insurrection.[11] Let me repeat that: a rebel tribunal made up primarily of slaveholders in a mostly free county somehow managed to come up with the gall to hang forty loyal Americans for the crime of refusing to take up arms in rebellion against their lawful government.

Given how dissent was handled in areas under rebel control–loyal Americans being forced to choose between either taking up arms against their own country or being hanged from the nearest tree by a kangaroo court–we should not discount the possibility that even in places where the historical record would appear to suggest near-universal support for secession, there was in fact a fair amount of silent dissent from those who feared–not without reason–that such dissent, if voiced, would be met by their neighbors with swift and brutal retaliation.

I could almost stop here and consider my point well made, that not all southerners during the Civil War were devoted Confederates, and as such southerners today might consider themselves free to reject any notion that they should consider Confederate history to be, ipso facto, their history, their heritage as southerners, but seeing as today is February 15, I would be remiss if I did not go into some detail on the historical event which precipitated this writing. Here I am referring to the Kinston Hangings, which took place throughout the months of February and March of 1864, with thirteen lives claimed in a single mass hanging on February 15, 1864.

Prelude

“Soon after assuming control of my district, I ascertained that there were among the non-slaveholding population, many who professed sentiments of loyalty to the Union… many of them had successfully resisted rebel conscription, and had never given their allegiance to the rebel cause. Very few of them were interested in slavery, and consequently had no reason for aiding the rebellion. They worked in their fields in parties, with arms near at hand, during the day, and at night resorted to the swamps for shelter against conscripting parties of rebel soldiers; and by thus constantly being on the alert succeeded in rendering unavailing all efforts of the rebels to force them into the ranks of their army.”

Account of Brigadier General Rushton C. Hawkins, US Army, written in early 1867 and included in his later compilation, An Account of the Assassination of Loyal Citizens of North Carolina, for Having Served in the Union Army [12]

The Union, with its command of the sea, succeeded in reestablishing control over many coastal areas relatively early in the war. By February of 1862, this included many towns along the coastal plain of North Carolina.[13] It was from these areas, restored to the jurisdiction and control of the lawful Union government, that the First and Second North Carolina Union Volunteer Infantry regiments were raised.[14]

Two years later, with the Union still in control of much of the coastal plain, the Battle of New Bern was fought. It was a relatively minor affair, lasting from February 1 to February 3, 1864, and consisted of an attempt by rebel forces under George Pickett to capture the town of New Bern, North Carolina. Fittingly, seeing as Pickett is a man best known for his failures, the battle was a Union victory. The singular “accomplishment” of the rebels was to capture some men of the North Carolina Union Volunteer regiments mentioned above.[15] One might think that a rebel traitor would realize he had no authority–legal, moral, or otherwise–to put another man on trial as a traitor, but if the subject of inquiry is the rebel leader George Pickett, one would be wrong. He held no such scruples.

Dubious Jurisdiction

The grounds for rebel jurisdiction–and Pickett’s in particular–were dubious, and that’s even allowing, for the sake of argument, that a rebel government can exercise jurisdiction in furtherance of insurrection (it cannot).

Much was made, according to witnesses at a later court of inquiry, of the fact that these men were supposed to have been conscripted into rebel service and thus, not only were they “traitors” to the rebellion, but deserters too. And that these men were supposed to have been liable for three years’ service in rebel units seems to have been especially persuasive to Pickett.[16] But recall that, under the Conscription Act of 1862 and its amendments, the rebel cause was so devoid of willing volunteers that anyone between the ages of 18 and 45 was supposed to be liable to serve, no call-up required.[17] By such standards, if a man was fit to carry a rifle and walk a mile or two without collapsing, he was not only fit, but in the eyes of rebel leader Pickett, obliged to fight for the preservation of slavery–especially if he didn’t hold sufficient slaves to exempt himself from that duty.[18]

Even moving past the overall lack of legitimacy of the rebel government and its acts, trying these men as traitors and deserters was questionable on three grounds at least:

First, it’s clear from the record testimony that at least one man, Elijah Kellum, never enrolled in any part of the rebel army–not even among the local defense forces that others joined–and certainly not in a general service unit. And to be clear, he had not sought to evade service, but had actually tried, willingly, to enlist on two separate occasions, but was in both instances denied after being found physically unfit. As one witness put it, “he had no constitution… no medical board would accept him,” but he “deserted” to the Union lines at some point, and that was enough to see him hanged.

Second, even those nominally fit for service were never more than members of a local defense battalion that owed its allegiance to the state of North Carolina, not the rebel government in Richmond. When they were unlawfully ordered from their homes to join a “general service” regiment of the rebel army, not being slaveholders themselves and having no particular stake in the rebel cause, these men sought the protection of the Union Army. They duly enlisted in federal service to defend their homes from the real threat to their liberty: the rebels. [19][20] Although this may seem a self-serving and highly suspect defense in the face of a charge of desertion from the rebel army, testimony given at both the rebel court-martial and the post-war court of inquiry bears this out:

“…on account of the annoyance I gave,[I] was ordered with my command to Kinston, North Carolina… and my men to be given the choice between volunteering for general service or be sent to the conscription camp.”

“The court asked me if [Clinton Cox] ever belonged to my company; my answer was yes; and asked me if he deserted; I told them no, for I did not consider desertion from a local company desertion from rebel service.”

Sworn testimony of Guilford W. Cox, Captain of a company “in local service” and witness at the court-martial of Clinton Cox, before a Court of Inquiry into the Kinston Hangings, November 9, 1865 [21]

Z.B. Vance, who was Governor of North Carolina at the time of the hangings, offered testimony to that effect as well:

“I am inclined to think the confederate government did not keep faith with those local troops… I did at various times make appeals to confederate authorities in behalf of men of this State. These men were enlisted entirely for local defense, and [yet] every effort was made to transfer these organizations into the regular service of the confederacy when they were found to be worthless… [I]n these instances of Nethercutt’s battalion it was a violation of their enlistment agreements.”

Sworn testimony of former Governor of North Carolina Z.B. Vance before a Court of Inquiry into the Kinston Hangings, March 2, 1866 [22]

What is particularly noteworthy about Vance’s testimony is how it highlights the total lack of respect shown for states’ rights within the Confederacy, with the rebel army seeking to force local North Carolina defense battalions into general service by the point of a bayonet and under threat of a hangman’s noose, and with jurisdiction being exercised by rebel George Pickett, a Virginian headquartered in Virginia, over men subject to the jurisdiction of North Carolina. Indeed, testimony at the Court of Inquiry suggests that although these men were of North Carolina, their “crimes” were alleged to have occurred in North Carolina, and they were held and tried in North Carolina, only Virginians presided over their sham courts-martial.[23][24] This outcome was thus an effrontery to the sovereignty of North Carolina and lays bare and exposes as fraudulent any notion that secession was about preserving states’ rights–unless that right had to do with the preservation of slavery.

Finally, it didn’t really matter whether these men had ever served in the local defense forces or the rebel army, and that’s even granting that a rebel court acting in furtherance of insurrection could ever exercise legitimate authority (which, again, it can’t). That is because, one way or the other, these men were Union soldiers at the time of their capture. They were thus entitled to fair treatment as prisoners of war, even in the hands of rebels. At worst, they were “misguided” at the time they aligned with the insurrectionist government–that’s if they ever did–but then “repented, and returned to [their allegiance as citizens of the United States] again.” [25]

“I do not recognize any right in the rebels to execute a United States soldier, because, either by force or fraud, or by voluntary enlistment even, he has been once brought into their [rebel] ranks, and has escaped therefrom.”

Major General B. F. Butler, in a letter to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, on correspondence related to the Kinston Hangings between rebel leader Pickett and Major General Peck, April 14, 1864 [26]

Pickett, for his part, had frequent correspondence with Major General John J. Peck and Brigadier General J. V. Palmer of the Union Army in the lead up to and aftermath of the February 15 executions. In a letter dated February 13, Peck provided Pickett with the names of “fifty-three soldiers of the United States government” believed to have fallen into rebel hands at New Bern, and advised him that these were “loyal and true North Carolinians… duly enlisted in the 2d North Carolina Infantry.” He urged that they be treated as prisoners of war, as was their due.[27] But sham trials were already complete, and many of the men hanged by the time Pickett acknowledged this letter. Going by Pickett’s reply, dated February 17, it is unlikely that Major General Peck’s pleas for decency would have made any difference, even if received ahead of the executions: the men were known by their uniforms, the circumstances of their capture, and their own words to be Union soldiers. Indeed, that formed a key part of the charges against them.[28]

The Kinston Hangings

The dubious nature of Pickett’s jurisdiction not withstanding (rebel leaders seldom concern themselves with such “trivialities” of law), twenty-two men at least, and possibly more, were tried by sham courts-martial and hanged throughout the months of February and March, 1864. Most of the known victims–precisely thirteen of them–were hanged together from a single gallows on February 15, 1864. [29] The purpose of this mass execution was, in the estimation of one Union officer familiar with the events and the inquiry into them, “to terrify the loyal people of North Carolina; to make them subservient to the scheme of rebellion, and to bring contempt upon the Government its victims represented.”[30]

What follows are the actual words of witnesses to the events leading up to and in the immediate aftermath of the executions, offered in sworn testimony before a Court of Inquiry after the war. They are now part of the Congressional record, bound together and memorialized with other correspondence related to the hangings, in a collection fittingly entitled Murder of Union Soldiers in North Carolina:

“…Colonel Baker… came to my residence while my husband was in prison, and took my horse, and ordered soldiers to take my provisions.

“They kept me under guard at my house in Jones county, three days after my husband was executed. My husband was hung at Kinston… I was present but did not see him hung; I could not look at him. I knew he was hung because I received his dead body after he was executed, and herd the scaffold fall under him.

“…the [bodies] were partially stripped, except their under-clothes. Some entirely.”

Catherine Summerlin, widow of Union soldier Jesse James Summerlin, testifying on October 31, 1865 [31]

“He had nothing on but his socks; I could not take home my husband’s body for want of a conveyance. I… sent my son, aged 15, and nephew, aged 17, after the body; could get no one else to go. It was a week before I could obtain the body. My son found the body a week after the execution in an old loft… The guard refused to let the body go until permission was given by the doctor. Plenty would have been glad to have assisted me, but did not dare for fear of being called Unionists.

Nancy Jones, widow of Union soldier William Jones, testifying on October 31, 1865 [32]

“…he told me he had but four crackers to eat in four days… I then supplied him with food until his death.”

Celia Jane Brock, widow of Union soldier John J. Brock, testifying on October 31, 1865 [33]

“I had a brother-in-law hung… I procured an attorney to bring forward evidence in favor of him, but the court-martial would not admit him.”

Bryan McCallan, a stable keeper and a blacksmith, testifying on November 9, 1865 [34]

“A man about six feet high, stout, cross-eyed, told me that he volunteered to hang these men. He stripped the clothes from them the same night he hung them… He spoke in a boastful way; said he had got well paid for it; that he would do anything for money.”

Aaron Baer, a merchant, testifying on November 8, 1865 [35]

As even a cursory review of this testimony indicates, the rebel government, in addition to not caring too much for states’ rights that weren’t related to owning people as property, wasn’t much for individual rights, either–and that’s even for those who had the right skin color according to their own backward mores. There were people living in fear of being accused as Unionists (as if that was such a great crime–to be for the Union), widows with children being deprived of their meager possessions without due process of law or compensation, and men being denied representation at trial, starved awaiting cruel and unjust punishment, deprived of life and liberty without due process, then stripped naked as a final humiliation in death.[36] To cap it all off, there’s this exchange around the testimony of one J. H. Dibble, a carriage manufacturer who had been a resident of Kinston, North Carolina for twenty-two years. Not much new light shed on the hangings, but I think it says a fair amount about the overall oppressiveness of the rebel regime:

Question. By whom were you imprisoned?

Answer. By the confederate authorities.

Question. What were you confined in prison for?

Answer. I do not know, unless it was my northern birth.

J. H. Dibble, a long time resident of North Carolina imprisoned by confederate “authorities,” testifying on November 2, 1865 [37]

The record is silent as to the sufferings endured by the thirteen men hanged on February 15, 1864, in the interval between when the trap was sprung and the last expired. With such a spectacle–thirteen men dropped all at once from the same scaffold–it’s unlikely they got much more than a foot or two of travel before they came to the end of their ropes. It is almost certain that some men, at least, had to endure a slow death by strangulation, and all for the crime of supporting and defending the Constitution of the United States against insurrection and unlawful secession: rebel “justice.”

The Aftermath

The rebels would go on to lose the war, of course, but that wouldn’t stop the rebel George Pickett, in the immediate aftermath of the February 15 hangings, from engaging in a witch hunt for Union sympathizers in those areas still subject to his unlawful control. When, on February 17, he finally replied to Major General Peck’s humanitarian letter, urging decent treatment of the North Carolina men, he had the impudence to express his “thanks” for the “opportune list” of names.[38] Given that the month of February was not yet done, and there were more hangings yet to come, it is entirely plausible that, far from inspiring fair treatment of the named men as prisoners of war, it served as evidence to be used against them in sham trials, taken by Pickett as license for further hangings.

The Reverend John Paris, whose commentary on the hangings opened this writing, did his part, too. If he is to be believed, not only did he minister to the Kinston Hanging victims in the days and hours before their deaths–even unto the scaffold–he coerced them into giving up the names of those who had “seduced them to desert.” He then gave those names up to rebel leaders, having no doubt that they would be “properly attended to,” with all the sinister undertone that implies.[39][40][41]

An article for the Weekly Confederate, published in Raleigh just two days after the mass execution, described, seemingly without irony, the “disgraceful end” brought about by the “great” and “shocking crime” of “deserters to the enemy.” In his bloodlust, the writer went so far as to suggest that authorities might “search the press” (consisting of competing newspapers) that might have “exceeded the liberty of the press” and thus persuaded “these poor, deluded men” with their “pernicious counsels” to commit their “deplorable crime,” making them “an accessory before the fact” and thus just as guilty of “felony” as the “deserters.” [42] So much for freedom of the press. (And I do wonder if this anonymous author changed his tune about hunting down and hanging newspapermen for promoting treason when the war was over, and he was once more subject to the lawful authority of the United States government.)

Then there’s this report from the Western Democrat, ostensibly describing the final words and movements of some men upon the gallows at Kinston:

“They ascended the scaffold with a firm and elastic step, and seemed to bear up under their trials with much fortitude. They had but little to say, except Busick, who entreated his old comrades in arms to stand by their [rebel] flag and never desert it under any circumstances whatever, lest they should come to the ignominous end of those who were then about to die the felon’s death and fill a felon’s grave. ‘Oh, that I had never been born,’ one of the prisoners was heard to exclaim in his anguish a moment before the trap fell.”

From the “Western Democrat,” Charlotte, North Carolina, Tuesday, February 23, 1864 [43]

It was not uncommon for newspapers of the time to put words into the mouths of condemned men, to spin some sort of morality tale out of their execution. [44][45] But to do so here, with rebel traitors putting words into the mouths of Union soldiers, having them urge continued insurrection and cries of woe… Beyond the pale.

Rebel leader Pickett wasn’t done confessing to murder and treason when he sent his February 17 letter Major General Peck, either. In an exchange later that same month, after having received a threat from General Peck that he might retaliate against rebel officers in his custody if remaining North Carolinians were not afforded the treatment due to prisoners of war, Pickett persisted in asserting that “the men duly enlisted into the 2d North Carolina regiment,” were turncoats “taken in arms fighting against their colors.” He warned Peck that retaliating against rebel officers “[would] simply be… murder” because they were not “turncoats,” being rebels and all, but were properly prisoners of war–their treason against the United States of America and its people notwithstanding. As with the newspapermen above, he wrote this all seemingly without irony.[46]

But of course Pickett’s bravado lasted only as long as the war. Though he was pleased to mete out “justice” to poor farmers who weren’t too interested in fighting for wealthy slaveholding landowners, he fled to Canada just as soon as he found out there was an inquiry underway into the Murder of Union Soldiers in North Carolina (the same inquiry that provided much of the material for this posting). As the author of An Account of the Assassination of Loyal Citizens of North Carolina, for Having Served in the Union Army would later lament, however, no man would face justice for the Kinston Hangings. Pickett would return and, like so many other rebel leaders, accept a full pardon for his crimes.[47] To the extent Pickett is known at all by the vast majority of Americans alive today, it is for lending his name to the disastrous charge that a division under his command undertook at Gettysburg, but which he personally took no part in beyond ordering forward as he observed from relative safety.

As to how I think the rebel Pickett should be remembered… frankly, I think the Reverend John Paris said it best, here quoting his words–offered though they were in the original context of denouncing the men hanged by Pickett at Kinston–from the same sermon that I opened with:

Of all deserters and traitors, Judas Iscariot, who figures in our text, is undoubtedly the most infamous…

Reverend John Paris, in a sermon before Hoke’s confederate brigade at Kinston, North Carolina on February 28, 1864. [48]

…and we should add George Pickett to the list beside him, along with all the rebel leaders who levied war against the United States, in furtherance of their white supremacist aims and in perpetuation of slavery.

Now, it has been argued that since men like Grant and Lincoln were willing to deal liberally with the rebel leaders, to look past their crimes and issue pardons in a spirit of reconciliation, that we should follow their example into the present day. I don’t agree. Reconciliation as an exigency in the immediate aftermath of war is one thing. I simply cannot see why, with the space of a century and a half between us, those same exigencies that drove Lincoln and Grant to adopt a utilitarian policy of forgiveness should control us now. Today, when we talk about holding men like Lee and Pickett and Davis accountable, it is not in the sense of hanging them from the nearest tree (though they seemed happy enough to do that with men they considered traitors), but rather in the sense of reexamining their proper place in our history. Should it be atop a pedestal, as is literally the case in so many towns across the south, or should it be as subjects of reasoned criticism and cautionary tales? My vote is for the latter. Because when you put a man like Lee or Davis atop a pedestal and maintain him there, in a place of honor, that is not simply a matter of historical record: that says something about our present. It is indicative of what the community today chooses to recognize, implicitly or otherwise, as virtuous conduct. A monument to a pro-slavery traitor who led an insurrection against the United States is, every day it stands, a statement to all those around that says, in effect, “We support pro-slavery traitors who led an insurrection against the United States. We think such men and deeds are fit for emulation in the present.”

It must not be so.

Lost People, Lost History, Lost Cause

“I have never been a convert to the policy of our Government, relating to the rebels after they were compelled to surrender. The consequences of their acts cost the National Government nearly seven billions of money, the States nearly as much more and entailed a loss to of about three hundred and fifty thousand of valuable lives; besides grief, poverty and individual suffering which it is impossible to estimate; and yet, up to this time the men who brought about this great loss of life and untold misery to thousands of households, have escaped all punishment, and a majority of them, no doubt, feel that they are at liberty as soon as they regain sufficient strength, to undertake another rebellion.

“I have yet to learn any good results to the Nation, in consequence of this indiscriminate, senseless and unprecedented pardoning of rebels. On the contrary it has led them to believe that our respect for their individual superiority and bravery has caused us to sheath the sword of justice which should have fallen upon many of their necks…”

A letter from Brigadier General Rushton C. Hawkins, US Army, to Henry B. Dawson, November 1, 1870, describing the impetus for his compilation, An Account of the Assassination of Loyal Citizens of North Carolina, for Having Served in the Union Army [49]

Just because Grant and Lincoln saw the utility of swiftly moving past the fissures that led to insurrection–the treachery of southern leaders who ruled with an iron fist as they cowed their less well-off countrymen into fighting a war for the perpetuation of slavery–does not mean that we should turn a similarly blind eye to the historical reality. To continue to overlook the crimes committed by rebel leaders is to blot out the suffering of millions of slaves and poor white families who suffered under their heel, as if it to declare that their suffering never happened and they, in effect, never existed. To properly address the issues that are facing us today, the very real and persistent effects of centuries of systemic racism and generational poverty, we have to acknowledge that they do exist and are not historical accidents, rather they were and are all too often still the purposeful aims of those in power. Not all the villains of our past, set upon pedestals and cloaked in the auspices of “great men,” were Confederates, but how controversial should it really be to recognize that treason in the name of white supremacy is a bad thing?

We cannot change history–nor should we seek to try–but we can choose which elements of our past to emphasize, and how. To reject the legacy of the Confederacy–to decline to lionize these men who led an insurrection in which so many of their countrymen lost their lives–is not to reject one’s heritage, but to choose to seek out those element’s of one’s heritage that are worthy of esteem, and to hold those who have come and gone before us to proper scrutiny so that, where called for by the historical record, past failings can become the proper subjects of cautionary, not heroic, tales.

The Lost Cause myth was built upon the personal. In response to the bare historical record showing that secession was caused by a direct desire for those men in power in the southern states to preserve the institution of slavery, proponents of this myth will instead seek to drive inquiring minds to letters and recorded speeches, ostensibly representative of broader public sentiment, that express disinterest with or disdain for slavery, insisting that the war was really about taking a grand stand for states’ rights. Quite often, too, they’ll put forward letters from common soldiers, expressing a sort of patriotic fervor as they “defend their home” from invading yankees–never mind states’ rights or slavery, it’s about freedom.

The truth that I have sought to lay out in the preceding paragraphs–what tends not to fit within the narrative of the Lost Cause mythos–is that not all southerners marched in lock step to answer the call to arms against the Union Army. Many were, in fact–even in the deep south–loyal and devoted Unionists. For them, “freedom” meant to be able to avail oneself of the rights and privileges guaranteed citizens under the Constitution of the United States of America, flawed though it may be even to this day, and the thought of taking up arms against it was abhorrent to them. To insist that modern “southern heritage” must or even should include, as a subset, “confederate heritage” is a gross misreading of the historical record and totally ignores all the many “islands of blue,” whether the size of West Virginia, a Texas county, or even one man alone working in the fields with a gun at his side by day and retreating into nearby swamps at night for fear of rebel mobs seeking conscripts.

Efforts to dismantle the Lost Cause myth are not revisionist history. Rather, it is the Lost Cause itself which was and is revisionist history, perversely written by the losers and foisted upon the victors and the descendants of all under the guise of reconciliation. To properly dismantle this revisionist myth, we must strip away the gloss of “states rights” and “freedom” and focus on the ugly reality of an insurrection instigated by white southern elites. The history of the Confederacy was, when you strip away the Lost Cause framework and lay bare its foundations, a history of hate. It need not, and it should not, form the basis of southern heritage today.

Rebel leaders, to a man, misled poor white men and levied war against the United States of America in furtherance of the oppression of people of color. This was treason.[50] That makes them traitors: a label which they had no qualms about affixing to the names of the Kinston hanging victims. The sooner we can recognize this true history–that is, the sooner we can stop holding men such as Lee, Jackson, Davis, and all their co-conspirators in white supremacist insurrection in high esteem–the sooner we can properly grapple with the problems of our past and their lasting effects from a foundation of truth, not myth, and really heal as a nation.

Say no to the lie that the Confederacy represented anything but the most loathsome devils of our nature. Say no to hate. That’s the heritage I want as a southerner.